Ground Gas: The Lessons from Loscoe

In 1986, a bungalow in Derbyshire was completely destroyed by a landfill ground gas explosion, badly injuring the three occupants inside the home. This now famous and near-tragic incident served as a low-water mark in landfill management practices and site investigation.

We review the explosion, the lessons learnt and consider how far we have come in identifying and respecting the power and impact that ground gas from nearby landfills and old mines can have on property.

Background to the Explosion

The site at the village of Loscoe, near Heanor had been used as a brick works from the mid-nineteenth century until the early 1970’s. The quarry that supplied the clay was part-filled with inert waste products from the brick-making which ceased in 1971. Permission was then granted for the tipping of inert materials only by other companies through to 1978, when one of the companies purchased the site.

Prior to this in 1977, a licence had been granted to tip a wide variety of wastes, including 50 tons per day of untreated domestic waste. It took 7 years for the first signs of ground gas generation to become apparent. Lawns started to show crack-lines of dead dried-grass, and trees began to wilt and die in the surrounding gardens. The soil around the affected areas began to heat up, which was thought to be have been due to the presence of methane feeding bacteria.

Despite objections from residents in adjacent houses, which by the end of the 1970s had been built on all four sides of the quarry infill, extensions to permissions to increase the quantities of domestic waste tipped were granted. Residents had to endure ever larger amounts of vermin and flies.

As organic matter decays, methane is produced alongside carbon dioxide. The origin of the explosion has two root causes. The first was a fundamental lack of appreciation of how methane needed to be managed instead of hoping for the best through an “out of sight, out of mind” approach. The second was the catalyst, which combined with the lack of an engineered escape route for the gas created the perfect conditions for the explosion.

On the day that the incident occurred, Loscoe experienced its lowest day of barometric pressure for 25 years – a fall of 29 millibars in just 7 hours.

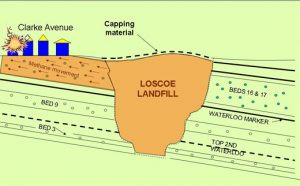

This allowed the methane, which had been steadily building up in the landfill, to escape through disused mining channels that ran beneath the site and led directly to the surrounding residential housing estate.

Explosion, Evacuation and Inquiry

Image courtesy of British Geological Survey

The gas moved into cellar voids beneath the properties. When a pilot light was ignited on the gas boiler timer in 51 Clarke Avenue early on the morning of 24th March 1986, the explosion completely demolished the house. It was a miracle that the residents escaped with their lives.

The resulting investigation showed two more houses had technically been unfit for habitation for the preceding nine months. The estate was immediately evacuated and 55 households were placed in temporary accommodation until the area could be made safe.

The investigations proved to be a Eureka moment for the regulatory authorities. For the first time, they recognised the hazard potential for large quantities of methane gas being generated by land-filled organic matter.

A Public Inquiry was carried out on the events leading up to the incident. It became apparent that signs of ground heating had been detected approximately 100m beyond the boundary of the landfill some years before the explosion, but had been misinterpreted as a shallow burning coal seam. Had this fundamental error been properly investigated, the Loscoe residents may have been protected from uncontrolled gas migration.

Following the Loscoe incident, best practice was changed to require venting and flaring of landfill sites capable of methane generation and also to require sites to be lined to prevent leaching of toxic material.

Derbyshire County Council monitored methane levels in the houses at regular intervals. Attempts were also made to draw the gas out of the tip by horizontal and vertical methane extraction wells. Across an installed grid of 17 wells, supported by a purpose-built pump and flaring unit, the landfill gas generated and extracted from the site was measured at 150-200 cubic metres per hour, at a 30-35% methane content.

A Tighter Regulatory Regime

Since the Loscoe incident, the regulatory and site investigation landscape has also changed significantly. Site operators were initially required to implement a series of alarms and other safety measures to enable site operators to monitor their operations and to prevent escapes outside site boundaries. Since 1995, UK landfilling operations have been regulated by the Environment Agency (EA), Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA), the Northern Ireland Environmental Agency (NIEA) and more recently Natural Resources Wales (NRW).

All waste operations are now controlled by one Environmental Permit, supported by a clear regulatory framework.

Many guidance documents have been published on the topics of ground-gas generation, migration and associated hazards since the Loscoe tragedy. The public inquiry identified the source-pathway-receptor model that is used today. It also identified migration drivers, such as falling atmospheric pressure, as a fourth factor that affects ground-gas contamination.

Improvements in Ground Gas Monitoring

Since 1986 there has been a steady evolution in monitoring equipment, techniques and the understanding of ground-gas behaviour.

Initially, monitoring wells were dug to assess gas concentration and borehead flow into the well. Some were open to the elements and next to useless as gases mixed with air and confused any readings of where the flow was coming from. The current best practice is given in BS8576: 2013. This includes a sealed head space where the ground-gases collect and can be monitored.

Where present, the depth to the groundwater should also be monitored and readings taken across a number of wells, recognising that ground-gas migration is frequently dominated by the horizontal permeability through strata.

There are two types of gas monitoring techniques:

- ‘Spot monitoring’ – the discrete periodic monitoring usually carried out using hand-held equipment by suitably qualified technicians who visit a site to take monitoring well readings at prescribed intervals; usually weekly or less frequently.

- Continuous monitoring – monitoring carried out by in-situ devices that record time-series data at a monitoring frequency that exceeds the frequency of change of the measured parameter. Typically, time-series data will need to be collected hourly or more frequently to be termed ‘continuous’. This is now widely adopted and has been used on thousands of sites in the UK and elsewhere.

In the last few years, continuous flow monitoring has become available and this provides a further line of evidence that can be used in ground-gas risk assessment.

Gorebridge Mine Gas Incident

But serious ground-gas contamination events still occur. In 2013, residents of Newbyres Crescent in Gorebridge, Midlothian, reported that they were having difficulty waking teenagers up from sleep more than normal. Residents also reported headaches, dry coughs, dizziness and anxiety.

Following council investigations, it was discovered that the housing estate, built between 2007 and 2009, did not have a membrane fitted into the subsoil to protect it from ground gas emissions from the abandoned coal mines below. Monitoring proved the gas to be carbon dioxide, an asphyxiant which is lethal in high concentrations and a clear cause of the excessive teenage sleep.

The only answer was that the estate, which originally cost the council £6m to build, had to be demolished and all 64 houses rebuilt once a gas membrane was installed, at a projected cost of £12M. For the residents, it meant relocation for 6 months while the works were carried out,

Following recommendations from the investigations, ground gas mitigation measures were made mandatory on all new residential and similar developments across all former mining areas in Scotland.

The report concluded that the seepage of CO2 into the houses in Gorebridge was a rare, complex and costly incident associated with old coal mine workings. This incident is, to date, probably the most serious such CO2 related incident in Scotland.

Secure Environmental Insight for your Client

While there is now far better understanding about the potential risks from ground gas from landfills and mines these incidents show how management failings and simple oversight can have potentially devastating consequences.

There are some 225,000 potentially contaminative sites across the UK, of which just 5% have been brought to the attention of Local Authorities to maintain their contaminated land registers. The past records for landfills sites are also incredibly patchy, with very few records of what went into former quarries in the 1970s and 1980s – two of our most environmentally polluting decades.

There are many housing estates like the one in Loscoe that sprung up around or on these old in-filled sites which were landfilled prior to the tighter regulation. The long term risk of ground gas emergence and contaminative leachate affecting groundwater abstractions used for drinking water or local watercourses can still pose a threat, as their histories are largely unknown. This is also relatively true of estates built into the 1990s, as the regulatory framework did not really kick in until after 2000.

These two cases show how we have thankfully moved on, but they both demonstrate the risks that have to be managed when landfills and mines are close to property. And even with effective management, building occupants still need to accept ground gas extraction and flaring or other treatment processes on their doorstep.

Penny Andrews, Operations and Compliance Director at Future Climate Info comments:

“It is unfortunate that one of the legacies of the industrial revolution in this country is the widespread surface tipping of contaminated by products, which was accepted practice well into the twentieth century. Using waste to fill the void spaces created by quarries was seen as the natural response to the ever-increasing amounts of waste created by industry and by the throwaway culture that developed in our society. The nature of household waste also changed throughout that period to include high proportions of the organic materials that create harmful leachates and gases as they decay.

Loscoe may well have been the turning point in the attitude of the nation. Thankfully we now have a thriving recycling sector and we have come to understand that landfill should be the very last option, however, we must still deal with the legacy of those historical disposal methods.

It is important to consider and understand the risks presented to us, our children and the environment by the contaminated and decomposing wastes that are hidden beneath our feet. In purchasing or developing any property, prior knowledge of the risks and liabilities can help an investor make informed decisions”.

It is important for Conveyancers to provide an early indication of risks from potential contamination for their client, whether they are a homebuyer or acquiring a site for development. A Residential or Commercial Environmental Risk Report will provide clear, forensic insight on the site history and indicate if the property is in close proximity to potentially contaminated land.

For commercial or larger residential developments or follow-on solutions for complex cases, fixed fee further reviews including the FCI Appraisal or FCI Walkover will provide a detailed assessment, helping to satisfy planning and development criteria for the consideration of contamination issues. Insurance and remediation solutions can also be tailored based on the site’s unique situation.

For more information, visit www.futureclimateinfo.com, call 01732 755 180 email info@futureclimateinfo.com

Try before you buy

To take advantage of a trial free order of your first environmental report, please complete the enquiry form and we will get back to you as soon as possible. We will need to take more details of the property or site and ask some more questions about your firm and the transaction.